I’ve been playing and watching sports for my entire life. I’ve basically been an encyclopedia for teams and players and stats for as long as I can remember. I thought I knew everything. There was no sports question I couldn’t at least pretend to know the answer to. Then in 2011, I read Moneyball, and everything changed. My brain was completely rewired. Since that point, I have held a largely dogmatic position on the “fallacies” of momentum, clutchness, hot and cold streaks, and basically all mental and emotional factors in sports.

Momentum, clutch factors, and hot streaks are separate entities, but they share a similar foundation. They purport that past short term results can have a large impact on future short term performance, and for that reason I will use them somewhat interchangeably. Most sports fans see them as valid components of analysis, but the data suggests otherwise.

My argument has been simple: there is no statistical evidence whatsoever that dictates that emotional or psychological factors have any significance in sports, or any other physical performance for that matter. The totality of data simply does not bear it. And so I have not seen the point in accounting for those factors when analyzing sports. I held this belief for a long time.

To say that I entirely disregarded these mental inputs is actually a bit of a stretch. I acknowledged that they had some relevance, but because of the statistical analysis that showed their lack of tangible impact, there was no reason to consider them when making any statements or predictions about teams or players.

To summarize, there is virtually no statistical correlation between recent past performance and future performance in athletic events. The recency bias that birthed terms like momentum, clutch, hot/cold, etc. is self-explanatory. These concepts are narratives that only form when analysis is severely lacking in complexity.

I am now restating my position on these concepts. I’ve recently realized how unnecessary it is to “believe” that they don’t have merit. The more rational leap from evidence to conclusion is to say “there is no evidence” and “we currently do not have enough information.” I will no longer claim to know what cannot be known.

What’s now apparent to me is that writing off momentum, clutch, hot/cold is a philosophy that lacks complexity as well. While there is no methodology at present time to detect whether a player (or more challengingly, a team) is in the midst of a psychological change that will impact performance, this doesn’t necessarily mean that we won’t have one in the future.

It’s a tightrope walk when labeling statistical conclusions as “lacking in information.” Statistics are the only way that we can wholly summarize sequences of events. So to say that there is more than what the stats show is usually unwise. However, certain cases can have indicators that suggest that insight is there to be had in the future, however far away that future might be. Statistics reveal everything, unless they don’t. Numbers never lie, except when they do.

My change in thinking has been sparked by a recent infatuation with brain chemistry and neural analysis. There is vast scientific research that suggests that the mind has a direct impact on the body (and vice versa), and we all perceive this to be true through our own experiences as well. It seems unreasonable to disregard this connection in sports just because it’s existence can’t yet be demonstrated on paper.

The reason that the data doesn’t show any evidence of this connection seems quite simple: we rely on results to determine whether a player is “in the zone” or has “momentum” or whatever term you want to use. We do this rather than using performance or process based metrics. There’s no question that elevated states of consciousness, like a flow state or meditative state, can increase performance in any realm. So shouldn’t we account for this fact when studying sports?

Very elevated indeed.

Results driven numbers are simply the easiest way to conduct analysis. Sports fans are at best lazy, and at worst simple-minded. Not inherently, but sports are an escape for most people, so excessive thinking within sports fandom is typically frowned upon. But if we really wanted to understand the significance of “in the zone” or “momentum”, we would need to actually study and monitor the brains of athletes rather than just the results of the athletes. Surely this would be far too complex for many sports fans to want to deal with.

Being “in the zone” shouldn’t be defined by simply making some number of shots in a row. It should be defined by an elevated brain state that would theoretically be expected to improve performance. We essentially need neuroscience to show occurrences of momentum.

Determining if a team (rather than a player) has momentum is an exponentially more complex problem. In the case of team streaks, we would need to measure the brainwaves of entire rosters, and in varying degrees based on the role of each player to the team (both in terms of performance and in terms of presence). It’s an extremely difficult task to say the least, but not necessarily an impossible one.

My stance has been that momentum and hot streaks “exist” but the evidence is not strong enough to grant them any meaning or usefulness. My new stance is that momentum and streaks exist but the evidence is not YET strong enough. We are looking at incredibly complex problems that require greater technology than is currently being used.

We know that there is no statistical evidence for momentum or other emotional factors in sports, but only based on the methods that are currently used to detect them. Perhaps brain scans will eventually reveal otherwise. Perhaps simply seeing success has some impact on future performance as well (a basketball player can gain confidence just by seeing the ball go in a few times). But what seems not merely possible, and actually overwhelmingly likely, is that there is much more for us to know than what the data currently tells us.

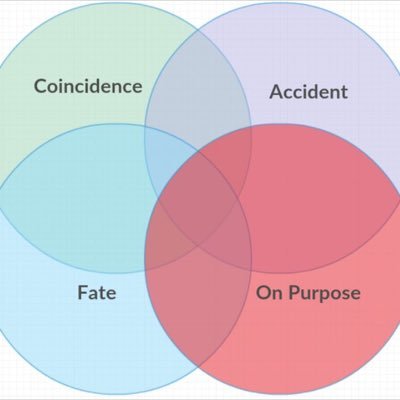

There is knowledge that we have. There is knowledge that we will never have. There is also knowledge that we don’t have as of now, but are likely to have in the future. At some point in the future, it seems likely that we will be able to connect sports performance with the brain in ways that we currently do not understand. We don’t get it now, but that doesn’t necessarily mean we won’t figure it out later.