Things to Think About is a column that is quite self-explanatory.

Is your vengeful attitude a sign of immaturity? Or something more?

“Don’t fight fire with fire.” (especially if you’re a firefighter)

“An eye for an eye makes the whole world blind.”

These cliches are drastically overused (just like basically all cliches) and I don’t intend to argue their usefulness. This is merely a reminder of a lesson that is widely employed in teaching children about ethics and morality. Its pervasiveness is tough to deny.

Children are taught from a young age that they should be strong when faced with conflict and that succumbing to violent impulses conveys weakness rather than strength. When parents and teachers encourage strength, they are generally talking about strength of the mind, not strength of the fists. Mental fortitude is fostered. Fighting is deemed unethical, unproductive, and immoral.

Yet somehow as we grow up, this moral lesson dissipates. Fighting permeates society, often stemming from trivial motivations. People fight at sporting events and at bars and at shows. People fight everywhere, and it’s naive to attribute fighting solely to “getting caught in the heat of the moment”. Fighting is more than just reactionary.

Take for instance the response by New York Rangers fans after this hit on goalie Henrik Lundqvist:

Many Rangers fans pleaded for retaliation (sourced from Twitter… thanks Twitter). They wanted Lundqvist’s teammates to fight back… to defend their collective manhood. The fans were obviously not personally slighted by the hit, and their outrage wasn’t brief enough to suggest it was simply impulsive. Rangers fans, even after having days to think about it, still felt that retaliation was somehow the proper course of action. Many Rangers fans are parents, I might add...

There’s an odd dynamic going on between my generation and my parents’ generation. It may be an oversimplification, but at least from my experience, adults seem more inclined to think vengefully than their children. These same adults were the ones who taught us about self-control. They taught us to show restraint and maturity. But far too often, their attitudes and behaviors contradict the lessons they once preached as hallmarks of integrity, character, and other evidently overused buzzwords.

Two years ago, I was near my apartment in Hoboken, New Jersey, when a random drunk guy who was walking past me punched me in the face… for no apparent reason. I fell against a nearby railing, gathered myself, and started yelling at him (I was a bit drunk too). I was mostly just disoriented and alarmed, having no idea what compelled this asshole to hit me. After a few moments of anger and confusion, I got my bearings and walked away...

I am wholeheartedly content with the fact that I didn’t fight back. Sure, I feel an occasional hint of lingering rage, but that feeling immediately subsides whenever I become fully aware of it. Would it have been better to hurt him? Break his bones? Decapitate him? Retaliation didn’t, and still doesn’t, seem like a practical answer.

Whenever I explain this incident to older people, there’s a strange prevailing reaction: they seem to prefer retaliation to the assurance of personal well-being. “I would’ve cracked the guy,” they’ll say. “How could you just let him walk away!?” The impulsiveness of this line of thinking is highly concerning.

So what’s really going on here? Have adults taught non-violence to children as a form of training wheels before we’re ready to defend ourselves in the “real world”? Are they giving advice they have no intention of following for themselves?

Perhaps the lesson of non-violence is well-intentioned, and just difficult to adopt in practice. Or perhaps too much of this “real world” experience has made many people too cynical and bitter to practice what they once preached.

Vengefulness is obviously not exclusive to middle-aged people, and perhaps it’s too general to say that an entire generation is more vengeful than another. What is clear, however, is that vengefulness is an impulse that just about every human has, and it’s one that certain people may have a diminishing willingness or capability to suppress.

What is the point of revenge?

Revenge is essentially payback. It’s about getting even for something, by violent means or otherwise. There is ample scientific research on the psychology of revenge, but it doesn’t take a dissertation to illustrate its roots. Payback satisfies temporary feelings of anger and helps to restore short-sighted “values” like pride and dignity. It boils down to a restoration and proclamation of manhood.

Getting revenge gives a short term high, likely because of the associated adrenaline boost. And there’s the obvious perception of “winning” that people love to achieve. Success is universally enjoyable no matter how you spin it. Winning at anything brings sudden emotional enrichment, and defeating someone directly, perhaps physically, is just a pronounced way to do it.

But while revenge has instant merits, there are obvious downsides that, upon further introspection, make it seem like a senseless proposition. First of all, if you fight someone, you could lose. That’s certainly a bad result. Fighting has potential costs: embarrassment, injury, or worse. Revenge is also fueled by emotion, so it's innately disjointed from logic. Vengeance is emotionally clouded, and therefore a deviation from the normal flow of decision making. It’s an inefficient way to think and behave.

Lastly, and perhaps most importantly, even when vengeful retaliation is successful, even when you put someone in their place, and even when there isn’t much damage, you still feel bad about it. When harming others, cognitive dissonance is usually inevitable. Even just thinking about revenge can be a psychological burden.

But even if it’s somehow true that revenge produces net-positive results for the perpetrator, you still have to question whether or not it’s moral. Surely the joy of causing harm to another person, even when they “deserve it”, is not an embodiment of a good moral code.

But it’s still possible for retaliation to be sensible.

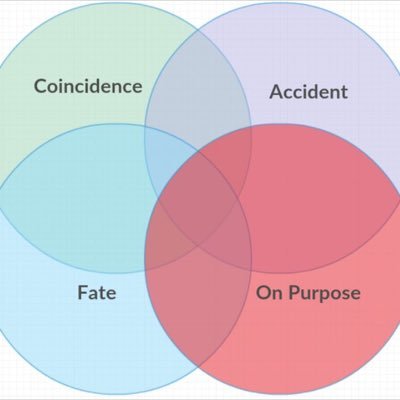

While retaliation is usually just about demonstrating toughness and dominance, I won’t ignore its occasional practical purposes. Sometimes retribution isn’t about about vengeance, payback, or emotional release. Sometimes it’s just a means to an end. Sometimes calculated revenge is intended to reduce future physical harm rather than increase it.

Intention is often tough to discern, and the distinction between malevolent and altruistic retaliation isn’t always obvious. Perhaps Rangers’ fans simply wanted to deter future hits on their team’s star player. Perhaps they wanted payback simply to scare opponents away from being reckless. It’s hard to say, but to me this seems like an easy cop out.

The key thing to think about, is whether your retaliation is honestly meant to do good, or if it’s just about revenge. If you’re merely vengeful or hateful, then maybe it’s time to start rethinking the approach.

A spontaneous desire for vengeance is just as inevitable as any emotion. It's wholly unavoidable. Anger leads to rage and rage leads to violence. But calculated, premeditated vengeance? That warrants further consideration.

Just something to think about.